13 April – 29 May 2021

Ogawa Kazumasa | Esaki Reiji | Kusakabe Kimbei | Adolfo Farsari and the School of Yokohama

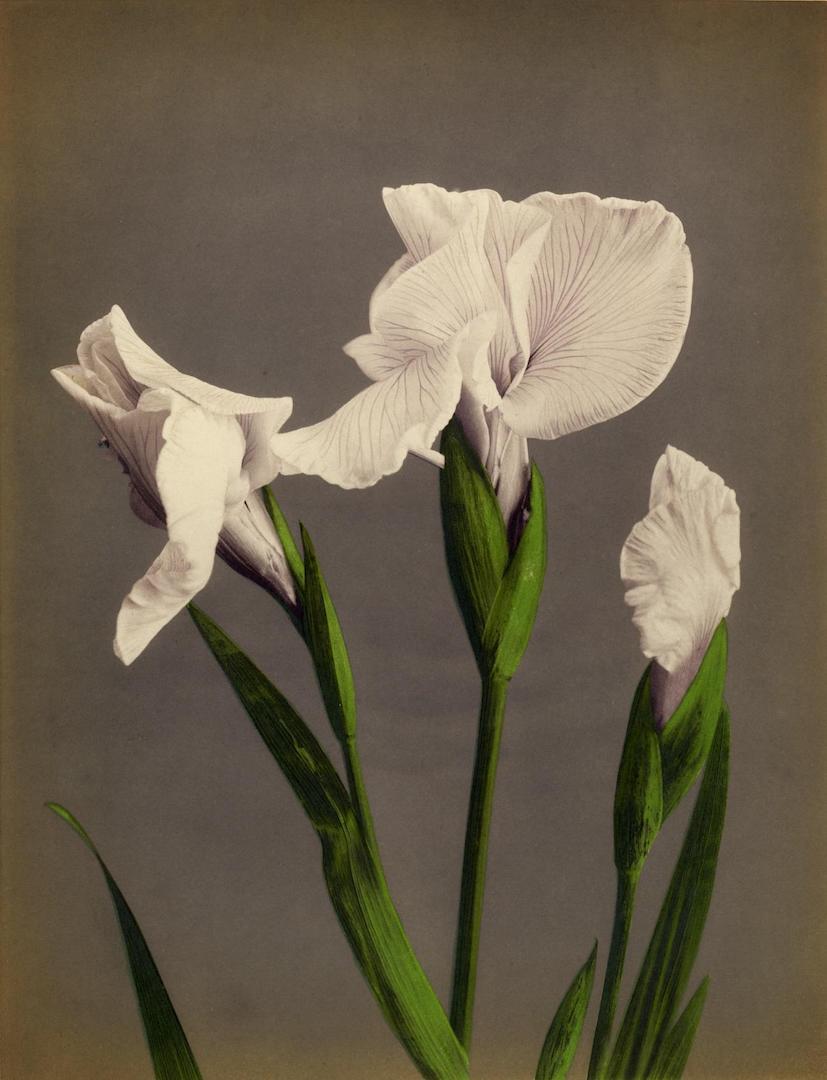

Flowers and gardens in late nineteenth century Japanese photography.

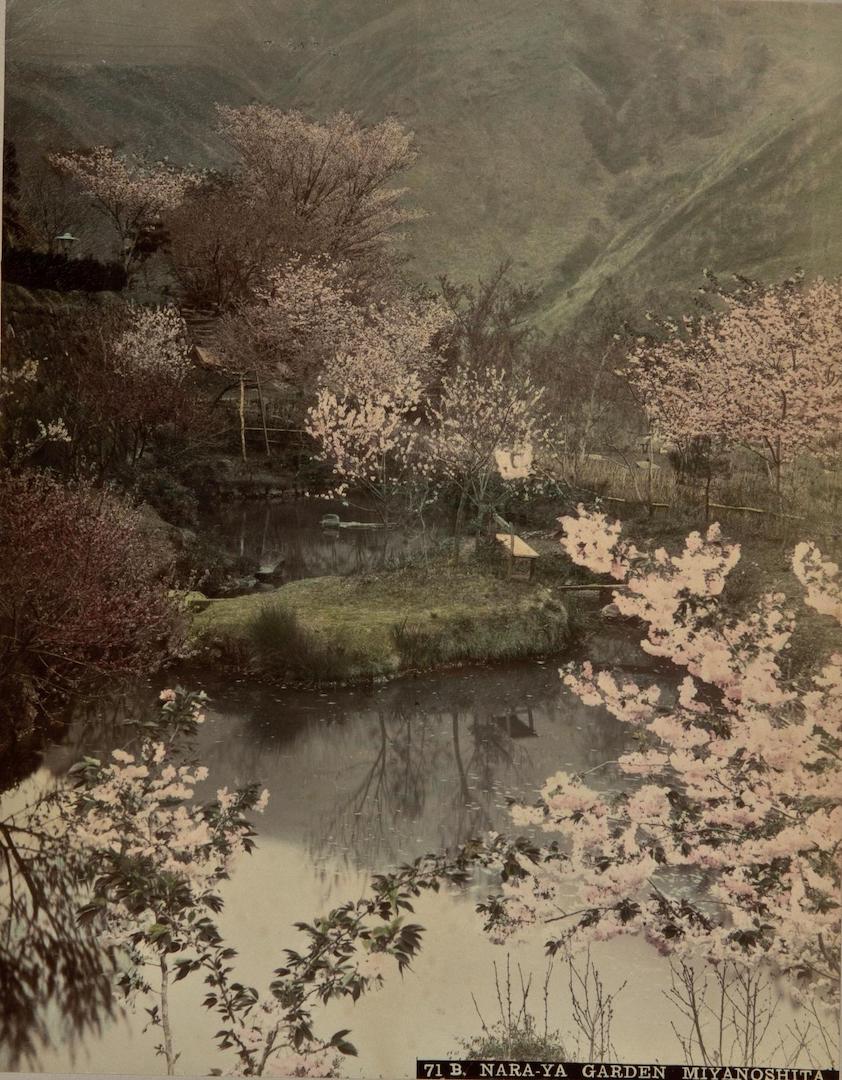

Japan in the second half of the nineteenth century was the site of a unique marriage. The Western photographic technique of the albumen print united with the traditional artistry of local painters who were able to apply colour to even the tiniest of surfaces.

The results were of an astonishing beauty and the subjects represented so life-like that it is difficult to distinguish the hand-tinted photographs from modern colour photographs.

Creating these masterpieces were a thousand European and Japanese artists who were responding above all to the need of the Western traveller to physically represent and take with them the memory of an extraordinary country, which the forced modernization of the Meiji period (1868 – 1912) was rapidly transforming before one’s eyes from a still medieval world into a modern industrial nation. Both from a technical and an aesthetic perspective, the style which would become known historically as the ‘School of Yokohama’, after its major centre of production, represents the pinnacle of nineteenth century photography.

The subjects of the photographs testify, sometimes even through the tiniest details, to the vision of a culture characterised by a research into the subtle harmony of elements: landscapes, buildings, interiors, scenes from daily life, portraits of men and women, even the subjective images of tree branches and flowers, give the sense of a world suspended in an affable aura of perfection, of an enchanting but fragile exotic universe destined to disappear at the dawn of the nineteenth century.

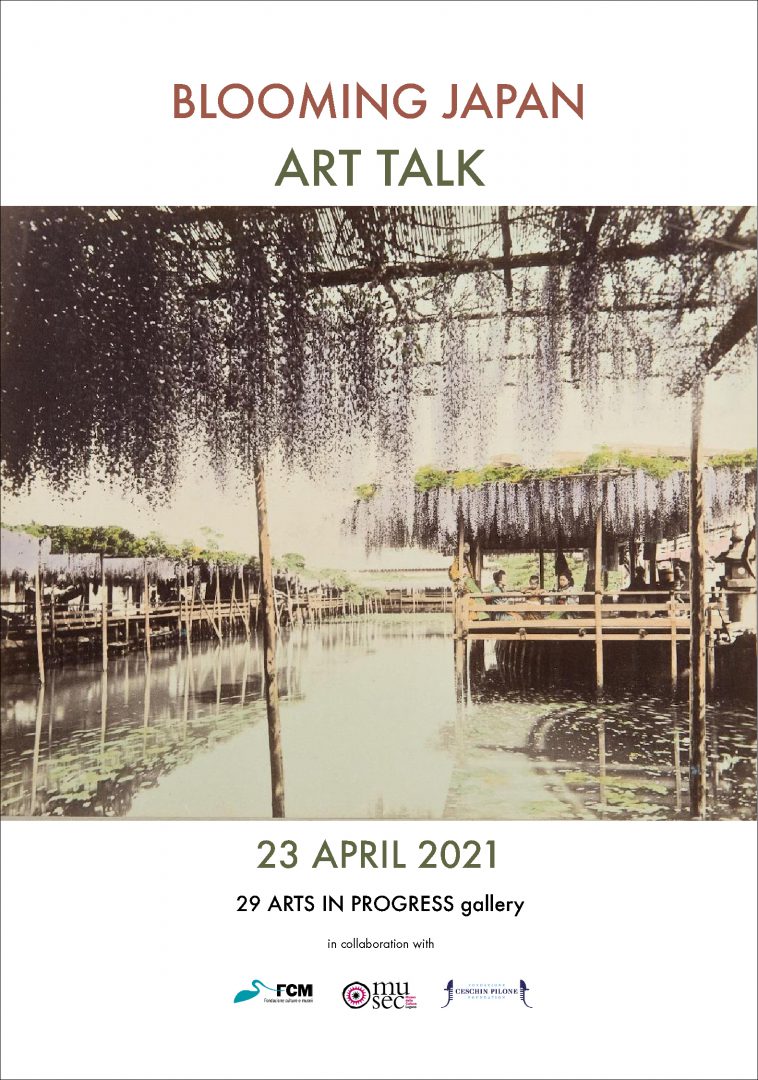

The exhibition focuses on depictions of flowers and gardens, both in albumen prints and collotypes. In Japanese culture, flowers appear in many artistic spheres, such as painting, woodcuts, decorative arts and poetry. Arranging flowers in a vase is in itself considered an artistic activity (ikebana).

The concept of “flowers” – intended in the wider sense to include shrubs, plants, dried branches, leaves, moss, but also understood as dew or snow – is interpreted as an important temporal marker, marking out the changing of the seasons in their incessant transience and following a cyclical vision of time – typical of Oriental philosophy and linked to the Buddhist concept of impermanence.

The passing of time is therefore perceived through minor changes such as the changing flora and fauna. This perception gave rise to an ancient calendar from the time of Edo (1603-1868), in use until 1873, that counted some 72 seasons within the four main seasons.

If flowers are associated with philosophical notions of time, gardens on the other hand are linked to a concept of space: whether these are the typical Buddhist gardens or traditional zen rock gardens, they reference local themes of creation recreating a cosmos in miniature through rocks, sand, ice, water and plant elements.